Looking to the future: what will a post-COVID-19 world look like?

Apr 17, 2020

Over the past week in Hong Kong, different segments of the community celebrated two major traditional festivals, Ching Ming (清明節) and Easter. Both events have deep cultural significance for observants, with long histories and cultural practices, going back some thousands of years. These events focus on remembrance and respect, but also serve to remind us of our present actions and the future. They bring families and faith communities together in different parts of the world. In 2020, these collective expressions of faith, respect, and tradition, have been disrupted in an unprecedented manner.

We need to travel back some distance in history to find similar times of enforced familial separation and geographic isolation. Some have drawn parallels with the experiences of those during previous world wars. Now, with nearly half of humanity under some form of government-mandated restriction on travel and assembly, including closed borders, closed recreational venues, even total lockdown, many of us have no doubt spent time wondering about the future, both personal and global, and the point at which life might return to something approaching normality. We wonder when we might return to a time and a world in which our collective nature is affirmed, movement is unfettered, and our health is not threatened.

I am not able to offer any medical or demographic advice about the pandemic virus, or the collective prognosis for humanity. It is a global phenomenon and therefore a global problem. We can all see the widespread erosion of trust that has now taken root around the world.

A form a ‘blame game’ has not helped and has probably hampered the necessary collective effort needed to find a medical solution.

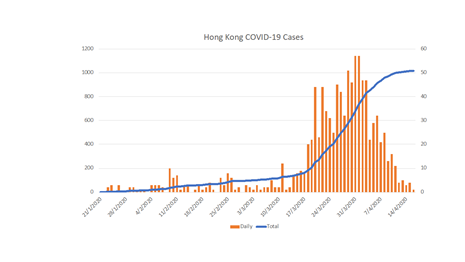

For many places, such as Hong Kong, that have now plateaued or seen a dramatic reduction in transmission of the virus, the political and economic consequences of further outbreaks are likely to be severe. Fear of a resurgence will act as a brake on the resumption of pre-COVID-19 human activity and movement, both nationally and internationally. As we read each day, this is already having a material impact on human welling in every community. While the virus is the root cause, isolation has been the immediate cure; it can only work in the short-term. Immunisation seems to offer the most promise as a long-term cure to this malaise that has so many dimensions beyond our physical health. We are told, however, that a reliable vaccine still lies some way off in the future.

|

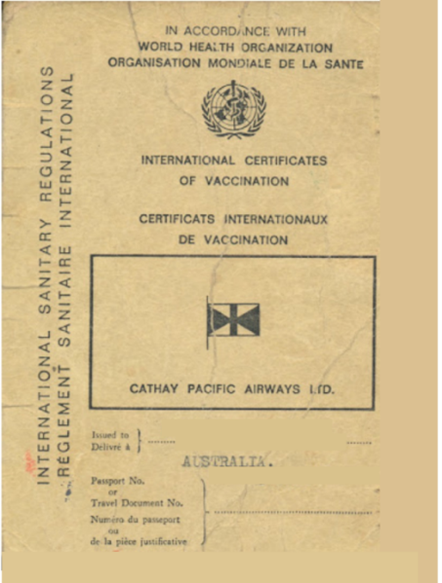

Some may remember the days of travel when international passengers were required to present both their passport and their official vaccination certificate, or Carte Jaune, for inspection when entering a foreign country. The Carte Jaune, a program developed under the auspices of the World Health Organization (WHO) after its founding in 1948, was intended to provide literally a ‘bill of clean health’ for anyone travelling (Yadav 2017, WHO 2020). Our passport establishes our official bona fides – in ‘good faith’; our Carte Jaune was intended to perform a similar function with respect to our health. Now essentially limited to a number of countries identified by the WHO as being at risk from the transmission of Yellow Fever, many travellers no longer need such a document. I must confess that I last used mine in 1979. Many may not have a Carte Jaune at all now. |

In order to re-establish good faith, to once more permit the free movement of humanity, we may see the widespread revival of immunization passports as the only practicable way of governments and communities re-establishing trust in the health of its citizens, residents, and visitors. This proof is and must be a precondition for the full resumption of human activity (Rainsy 2020). Such devices have been used in the past to verify that as individuals, we do not pose a threat to a community. I believe we can therefore expect to carry evidence of our physical bona fides for the foreseeable future.

In the absence of a cure, our immediate future, therefore, seems to point to constant vigilance and prevention. We can expect to have our temperature taken before entering places of business or learning. We should expect to carry personal protective equipment, such as surgical masks, as a matter of routine. We will find our understanding and practice of social distancing will take root in both our language and our actions. Societal institutions such as schools will adapt. Rites of passage will evolve. We will find ways of celebrating the purpose and spirit of social events in ways that reflect our acceptance of the need to share the burden of being alone, together.

Dr. Malcolm Pritchard

Head of School