On Wellbeing

May 2, 2025

One of the powerful social trends in recent years has been the focus on wellbeing in all phases of life. Across civilizations, countries, and communities, within industries and professions, families and friendship groups, we have seen an inexorable rise in the idea, indeed the social right, that we should be ‘well’. Wellness has become big business. We have wellbeing programs, policies, coaches, retreats, courses, and counselors. At an institutional level, the presence, practice, and promotion of wellbeing has assumed a strategic level of importance. Across institutions, entities, and associations, we have a keen and unwavering eye on what it means to be ‘well’.

In thinking about what this concept means in the real world, it is easy to be drawn into the very appealing ideas and ideals of wellbeing. We love to focus on the positives in life: to be optimistic, hopeful, motivated, engaged, happy, joyful, and healthy. We ascribe these and many more positive attributes to the general idea of wellbeing. The challenge often arises when we seek to detect or even measure these life-affirming attributes. They are highly subjective, but can also be mercurial, amorphous, even elusive.

Sadly, it is often the case that wellbeing is more starkly evident in its absence than its presence. We often recognize happiness, but only when it has vanished. We may experience fleeting joy but find it difficult to quantify what sustained or habitual wellness feels like. Health is another complex dimension of wellbeing. We may be healthy, yet remain unaware of its ‘presence’; more often than not, we feel more keenly the absence of health, through illnesses, or injury.

When thinking about wellbeing in schools, the dilemma is quite similar. We recognize the need to promote wellbeing among learners but find it difficult to identify the means of achieving this in a measurable way. We may use secondary measures, such as academic results, school attendance, or learner engagement as indirect evidence of wellbeing. For school-aged children, wellbeing can be a mercurial state that is driven or shaped by many factors. Personal, familial, and social forces play a huge role, as do academic and co-curricular activities. One of the tensions in school-based wellbeing is the time frame. Demanding programs may generate short-term tension or unhappiness while producing long-term results such as academic achievements or personal independence. Some events may bring about momentary happiness, like the cancellation of a homework task, but which make actually work against long-term wellbeing in the form of academic success!

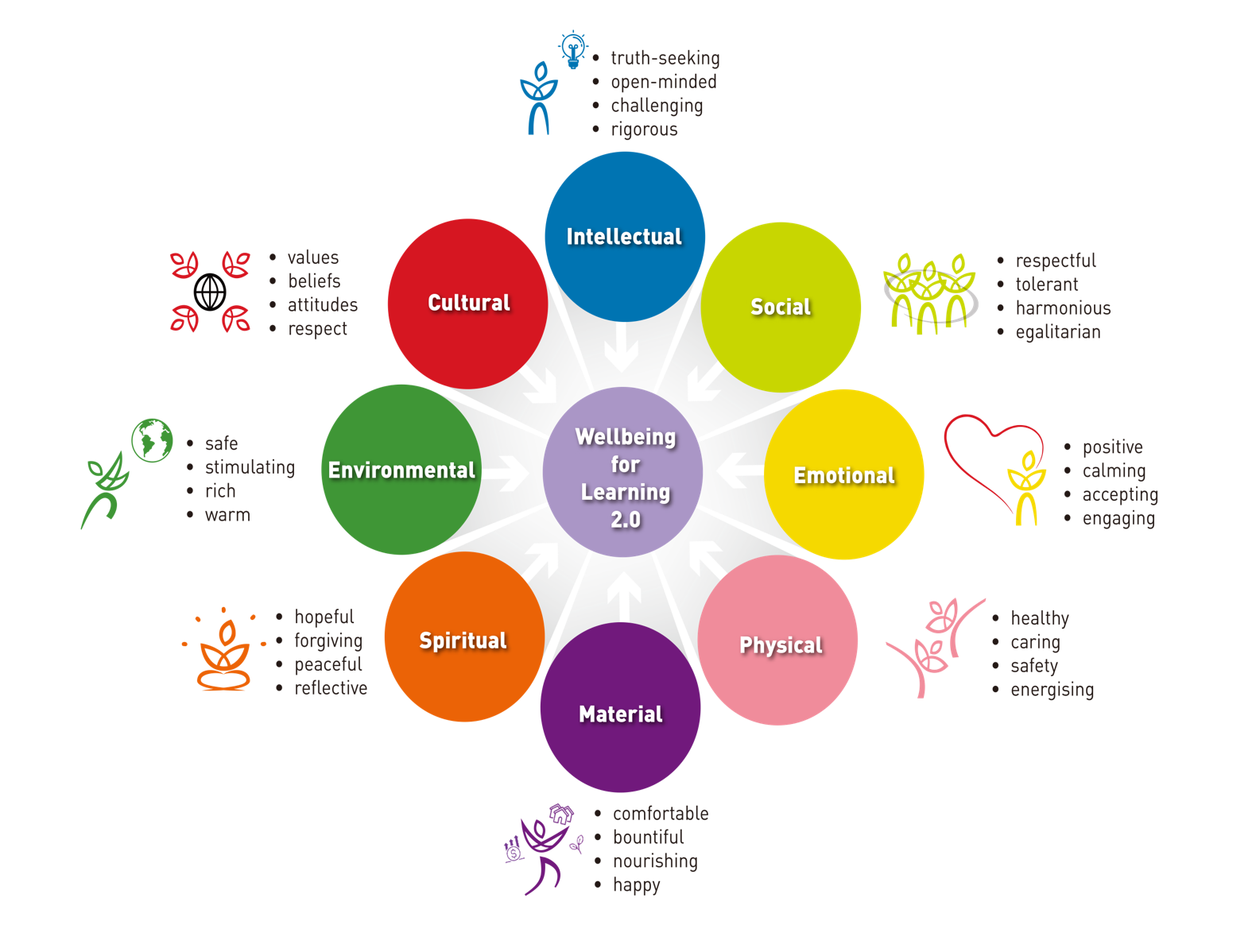

The following graphic reflects our attempts at mapping the parameters of wellbeing in a school context. While not exhaustive, this graphic does encompass both the visible and intangible elements of wellbeing.

It is not easy to develop a culture in a school community that acknowledges, promotes, and celebrates something that is often intangible or seen most clearly in its absence.

Another consideration is that wellbeing is not a unipolar state. In the same manner as other dichotomized pairs (e.g., night and day, good and evil, right and wrong, black and white), wellbeing has as its opposite the notion of suffering, heartache, sorrow, woe, anguish, distress, enervation, ill-health, discomfort, infirmity, frailty, and hardship. For some, the true meaning of wellbeing may only become apparent when it is lost. In schools, we often find ourselves deeply concerned with wellbeing when it is impaired or absent. How do we learn to recognize and promote wellbeing if its absence is the easiest thing to detect and measure?

As noted above, when viewed from a chronological or even biographical perspective, the whole notion of wellbeing becomes even more complex and nuanced. If we take the long-term view of individual health and wellbeing, we may find contradictions and compromises that involve ‘short-term pain’ for ‘long-term gain’. For example, the joy of true musical accomplishment is always built upon years of arduous practice and often stressful rehearsal and performance. The skills that bring joy in later life, both professional and personal, may only emerge on the foundation of relentless effort and unyielding commitment. Wellbeing may rest on a deliberate pattern of deferred gratification. We put off experiencing something positive in the ‘now’ in the hope that we will be rewarded with a greater positive outcome in the future.

Paradoxically, to become ‘well’ may involve experiences that are apparently antithetical to wellness. Safety may rely on learning to manage risk and danger; material wellbeing may involve some hardship; and intellectual wellbeing may entail the risk of errors and mistakes. Criticism, universally seen as a negative, may be necessary to achieve a future positive. Resilience, needed to remain positive in the light of life’s challenges, is typically the product of difficult experiences and failure. Even the universally lauded attributes of creativity, curiosity, imagination, and innovation may only be wrought in the crucible of trial and error.

It is a shared element of the human experience that ‘being’ and ‘wellness’ enjoy a complicated relationship. In our ‘being’, we may experience a full spectrum of emotions, including both the positive and negative dimensions of life. Perhaps a higher purpose is not the relentless and unsustainable pursuit of unipolar wellness at all costs. True wellbeing may well be found through striking a balance in which we live in a managed yet dynamic state of being well that is sustained and informed by rich life experience, both positive and negative.

Dr. Malcolm Pritchard

Head of School